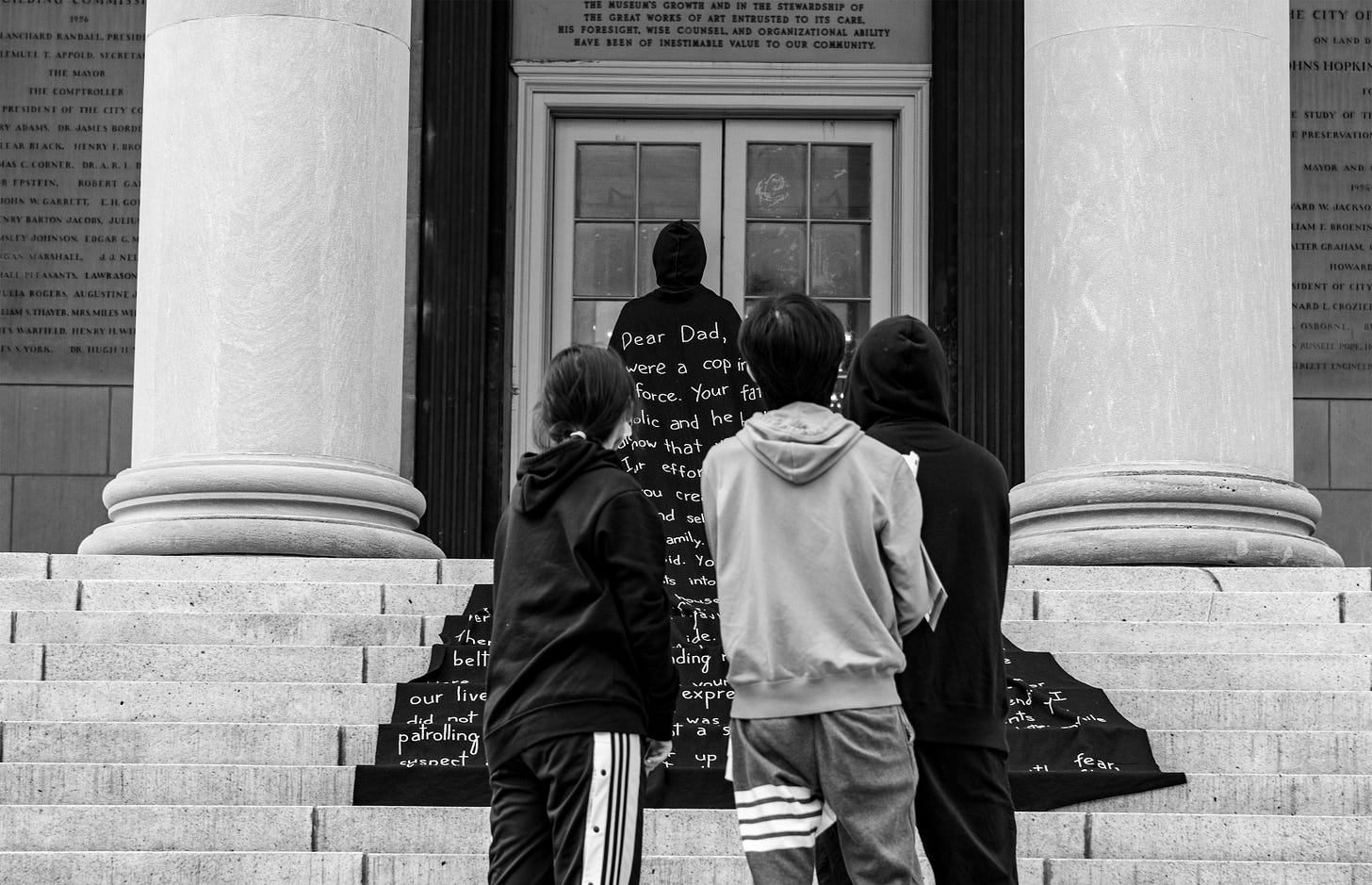

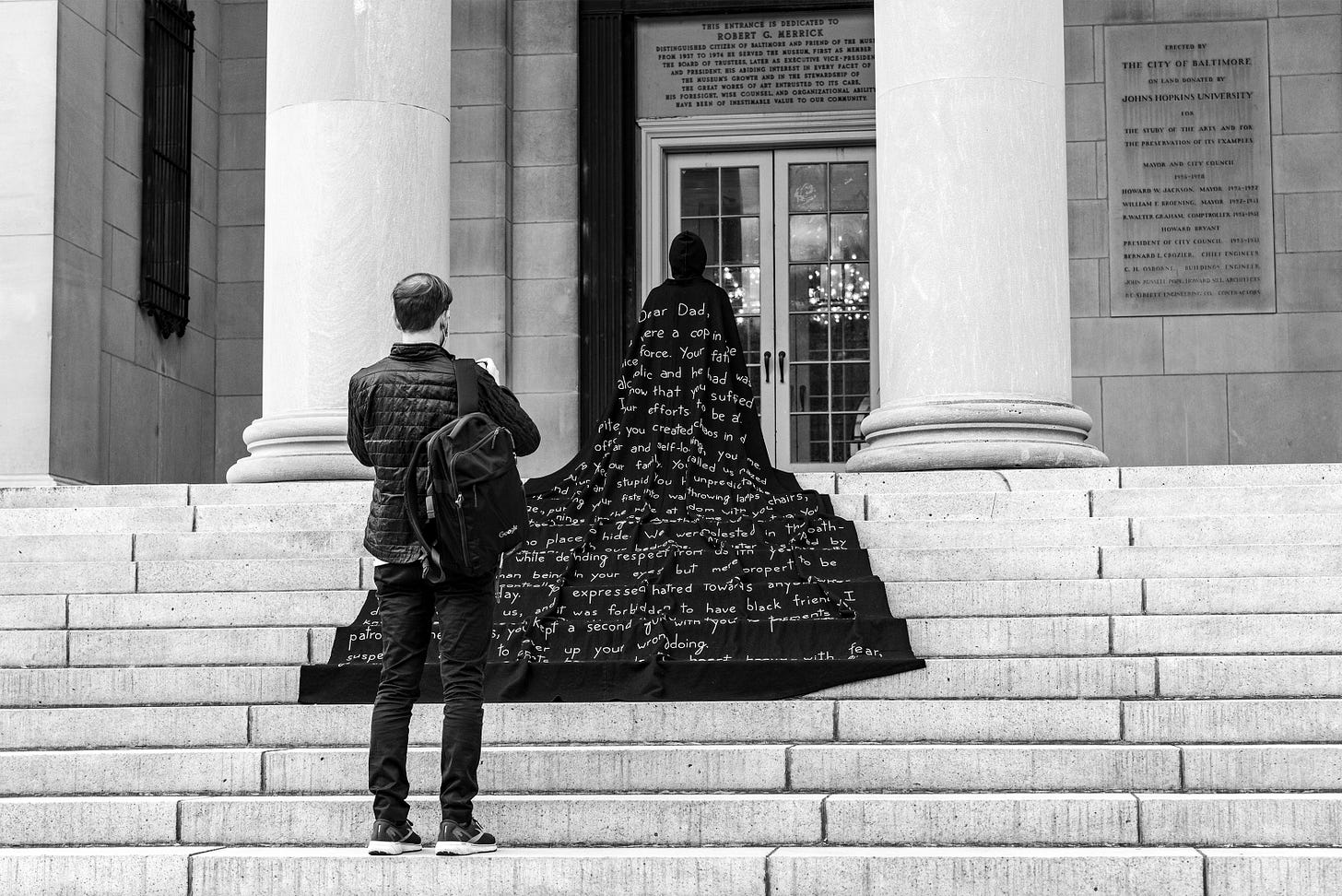

October 7th, Baltimore Museum of Art, 10 Art Museum Drive, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md. From 3:00 - 5:00 pm.

Photographs by Larry Cohen

Since I’ve made my performance at the Baltimore Museum of Art, a lot has happened. Mass shootings continue at a pace that has overwhelmed us with shock, and awe. I find this to be ironic considering George W. Bush used these terms to “shock and awe” Iraq in 2003 and onwards. It seems the war abroad has come home.

In other news, another young black man was killed with over 90 bullets fired by eight police officers because he ran from them in Akron, Ohio. More shock and awe. In the Highland Park mass shooting, the attacker was taken into custody without incident or injury. Jayland Walker, however, was gunned down with a barrage of bullets for a broken tail-light.

While not conflating these separate atrocities is very important, I’ve wondered why do men who commit mass shootings (predominantly white) get arrested with a reasonable and even gentle approach, while Black men/women are often killed instantaneously. In the past, out of ignorance and in my search for answers, I have wondered why do Black men run from cops. I remember wishing they wouldn’t run. Beginning with slavery, slave patrols, and then, Jim Crow laws, history has shown that Black men and women have often been humiliated, coerced, or brutally injured by police when they are stopped for misdemeanors. Cops will use vulgar language, threats to their safety, (get out of the f&%$king car with a gun pointed at his/her body) and harsh physical constraints (knee on the neck) for minor infractions. I can only imagine that these fascistic approaches and resulting grievances/trauma create injuries to the soul. In 1997, only five years after the Rodney King beating, Abner Louima was brutally beaten and sodomized with a broom in a New York police station bathroom. These histories are remembered. Re-membered in the body, in the limbs of communities and the social body politic.

Given the years of racial profiling and even more recently Stop and Frisk policies placed in U.S. cities, it would be reasonable for a Black man to run from cops when they pull him over. In a New York Times article, February, 2020, a reporter on the effects of Stop and Frisk wrote, “a young Black man was held at gunpoint while a cop passed his hand over his groin and buttocks before the police officer left without explanation. “ No explanation, no apology; cops feel they have the right to invade any body, at any time. “It happened to him over five times between 18-20 years of age.” The young black man stated, “Essentially, I incorporated into my daily life that I might find myself pressed up against a wall or on the ground with an officer’s gun at my head. For a Black man like me in his 20’s, it’s just a fact of life.” It is an understatement to say that the unpredictable nature of police behavior can cause great anxiety, just as my father’s predatory nature made me run, and hide as a child. If not exactly, I understand the immense panic of having a gun around when a person with authority and in a highly charged state of anger shouts out orders that are unreasonable.

The news in the last two weeks of the police killing and the sheer destruction of lives by a young man with an AK47 has created grave questions in my mind. Below is a list of mass shootings defined by the Gun Violence Archive as an incident in which four or more people are shot at (excluding the perpetrator) in one location at roughly the same time.

These horrific stories are beginning to feel like an old running clock. As I consider the pain and trauma of so many lives being taken or injured by AK47’s and by police brutality, I feel completely helpless. As I write about this now, I remember my own sense of powerlessness, and despair in my young life as I strategized a means of escape from domestic violence. Indeed, some of the mass shootings in America have occurred inside homes, where fathers killed their entire family and then committed suicide afterwards with a gun.

As I was heading to the museum, I noted my desire to be seen, and to create necessary, if not difficult conversations. I wondered, would anyone care? Would it help a witness to my story create some action in their own lives? The overwhelming evidence shows that most Republicans in Congress do not feel there should be more gun control, nor do they feel that police and the FOP, (Fraternal Order of Police) need to be held accountable when they harass or kill someone with a consuming force of gunfire. In Austin, Texas, 2021, lawmakers fell silent on restrictive gun measures, and actually passed “permitless carry” less than two years after the mass shootings in El Paso and Odessa took the lives of more than 30 people. Permitless-carry ruling is beyond infuriating. This is insanity itself.

John Berger once wrote, “Stories testify to the always slightly surprising range of the possible.” Stories are deeply interwoven into our lives, into our bones and flesh. We are our stories and then, sometimes-suddenly, we are not. For me, stories are the way of evolution.

Berger was hinting at how stories have portals of entry; sometimes it’s only a crack to the larger power of love. Can we gain any knowledge through our despair? I pulled my things out of the car, walked over to the café, and saw a few folks having coffee at the side entrance. I remembered my friend saying most people would be entering here rather than the neoclassical side of the building. I made a quick decision to set up my cape for the meditation near the cafe. I noted my breath. It was up high in my chest and I recognized my fear. I laid down my cape, got under it, and began my meditation.

I thought about the entry point of others reading my cape. What does it mean to enter someone else’s story? I looked at the BLM banner on the museum building, and I felt a deep melancholy that America still needed these signals, these cries for justice. That banner was a reference to too many stories of pain and death.

I was there for some time before a woman and a man approached me. She showed great expression through her face and I sensed her mind wrestling with my history. It was good to see her kind eyes; I felt a connection as we gazed towards each other.

Later a guard came by, stood behind me for quite some time. Would he try to remove me? I waited/meditated, waited, meditated, back and forth. He did not say a word and I was relieved.

I continued with my breath, looking, seeing, and staying still. Eventually, I sensed my boredom rising up, then an irritation at the boredom, followed by longing and fretting. I began to agonize over my decision to be here rather than the front side of the building. Heavy sighs began to ooze out of me. Very few people were coming along. Things seemed to move along too slowly. Where was my patience? Patience is an act of love, and I did not have it. A few others passed, and I realized that I have to be with the unknown over and over and over. Time went by, a construction of story-telling.

As I was meditating, I began to feel the pressure of my boredom become heavy and a great sense of futility rose from chest. Time felt like an eternity. More thoughts arose, more wavering in my mind left me feeling lost. I wanted something else, something active, something big… and out of my restlessness, agitation, and fear, a new thought, a new impulse arose. I wanted to take my cape to the front of the museum. This would be good, this would be right; it would create an image of great contrast.

I undid my buttons and walked over to the front side. As I did so, I noticed the security guard at the bottom, and I wondered if he would try to stop me.

Excitement and fear arose in my body; my heart beat faster as I pulled out my cape. I got down on one knee with the weight of the cape on my shoulders. The security guard didn’t budge and I was relieved.

Being there, I was now facing the elegant and grand doorway of the museum. This structure, taken from the past was a reference to our western lineage of patriarchy. Old Greek myths, and connections to democracy were symbolic through the architecture itself. The interior galleries held images of imagination, and creative risk. This is why museums are important to our humanity, and our connection to each other. I also began to realize that another portal was actually behind me, in the cape, in the letter. Art is an imaginative and necessary act, a way to know ourselves more deeply by entering unknown, and at times, frightening worlds. More pedestrians came and went, came and went. Maybe they could enter my story and not be too afraid.

I remained steady in my meditation, not knowing who or what was behind me. I’ve come to accept this practice and it allows me to let go of any outcome.

I was close to ending my two-hour meditation when a woman and man approached me with worry on their faces. He pulled out his badge and said he was head of security. He asked me if I had curatorial authority to be there. I said no. He asked me to leave, and I wanted to know if they had read my cape. They said yes. I was grateful that at least they’d taken some time to look at my embroidered letter. I mentioned that the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Seattle Museum of Art, and the Walker Art Center had let me kneel for the entirety of my performance. I wanted only 10 minutes more. He asked me to leave at once. I realized he wasn’t going to change his mind. And I also sensed a openness in him, so I gave him a card with a link to my project.

I packed up my things and walked to Larry’s car, torn between my desire for acceptance and angry feelings of rebellion. More questions arose in my mind about my hometown for which I did not have answers to. I’d begun to wonder how much longer would I need to bring out my cape. When will our violent country finally come to it’s senses. I went back to Larry’s car and he drove me home.

Later in the week, I’d received a surprising email from the head of security. In his note, he wrote,

Thank you for sharing your card today outside of the museum so that I could learn more about the cape…...I read the letter to your dad.

It is painful to know how you suffered. You should have been given love and protection.

Travel safely,

I was moved by his decision to reach out and I couldn’t help but be struck by this line of thought. “You should have been given love and protection.”

Isn’t this what the Black Lives Matter movement is asking for? Isn’t it their human right to feel protected and loved by fellow police officers? Unfortunately, and all too often, police arrive at tense scenes with heavy weaponry, and a highly militarized approach towards Black men and women. The Police expect great danger.

Ironically, it is the mass shooters ( mostly white ) who are terrifyingly dangerous. They have fueled their lives with hatred, and vengeance. Their horrendous acts of violence begs us to ask what is missing in their lives? What void is so large that an inner war seethes in their bodies and propels them to become killing machines. What are we going to do with so much pain as American citizens? Once, at a meditation sitting, one of my teachers struck me with these words, “ There is no US vs. THEM…. there is only US.” He is right. Shock and awe did not work in Iraq, and it doesn’t work at home either. I felt a connection through that email with the guard from the museum. Like many police, he could have dismissed me entirely. The fact that he took a little time and reached out to me is a crack in the bewildering story of violence. His words have given me a little more buoyancy, more possibility in my mind and heart.

So good to find this thoughtful reflection in my email inbox. Thank you for continuing to bear witness to the violence that surrounds us. . . and for telling the stories of how the cape sometimes opens a crack to let in the light. Sending love.