October 3rd, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Pkwy, Philadelphia, from 3:00 - 5:00 pm.

Photographs by Annie Lesser

Philadelphia is a real brick and mortar town with post-industrial ghosts. When I headed into West Philly on October 2nd, I saw vacant buildings, boarded up windows, and abandoned machinery rusting in empty lots. There were also signs of gentrification. The old brick houses were reminiscent of my home town, Baltimore. Seeing the urbanscape not far from the old Schuylkill Yards reminded me of blue-collar workers, people who worked with their hands, and were mostly straight talking. The Philadelphia Museum of Art is an old-world museum too, with a collection of over 240,000 works and a long historical connection to Europe.

In the 80’s, I lived not far from Franklin Parkway when I was attending Moore College of Art, so I visited the museum often. Usually, I went there to see the Abstract Expressionists’ works on the first-floor galleries. Having come from Europe after WWII, many of these artists had been deeply disillusioned if not traumatized by the war. Their paintings were monumental, gestural, and direct. The work was Avant-garde; knocking out all subject matter, and it felt American in a cowboy kind of way. The raw emotional energy found in their vast canvases had given me hope in my youth, yet I felt my rising nostalgia for that time in my life create a conflict in my mind. During the years I’d lived in Philly, too, the police bombed MOVE on Osage Avenue, burning up two blocks of a neighborhood, 61 houses in total, and killing African American families including five children. This show of outrageous force would give Philadelphia the sobriquet of the “City That Bombed Itself.”

When I arrived at the steps of the museum, I could not miss the crowd surrounding the statue of “Rocky,” a cinematic figure, who rose to the heights of boxing by utter force of will. Stallone, in one of his most famous roles, created an iconic scene at the museum plaza raising his fists into the air, jumping up and down in triumph. While the film has a schmaltzy feel, the story has connected with millions of Americans. I was enamored by Rocky and his story as a child. He was a wounded, uneducated, brutish guy who struggled for his dignity. He also had moments of real vulnerability.

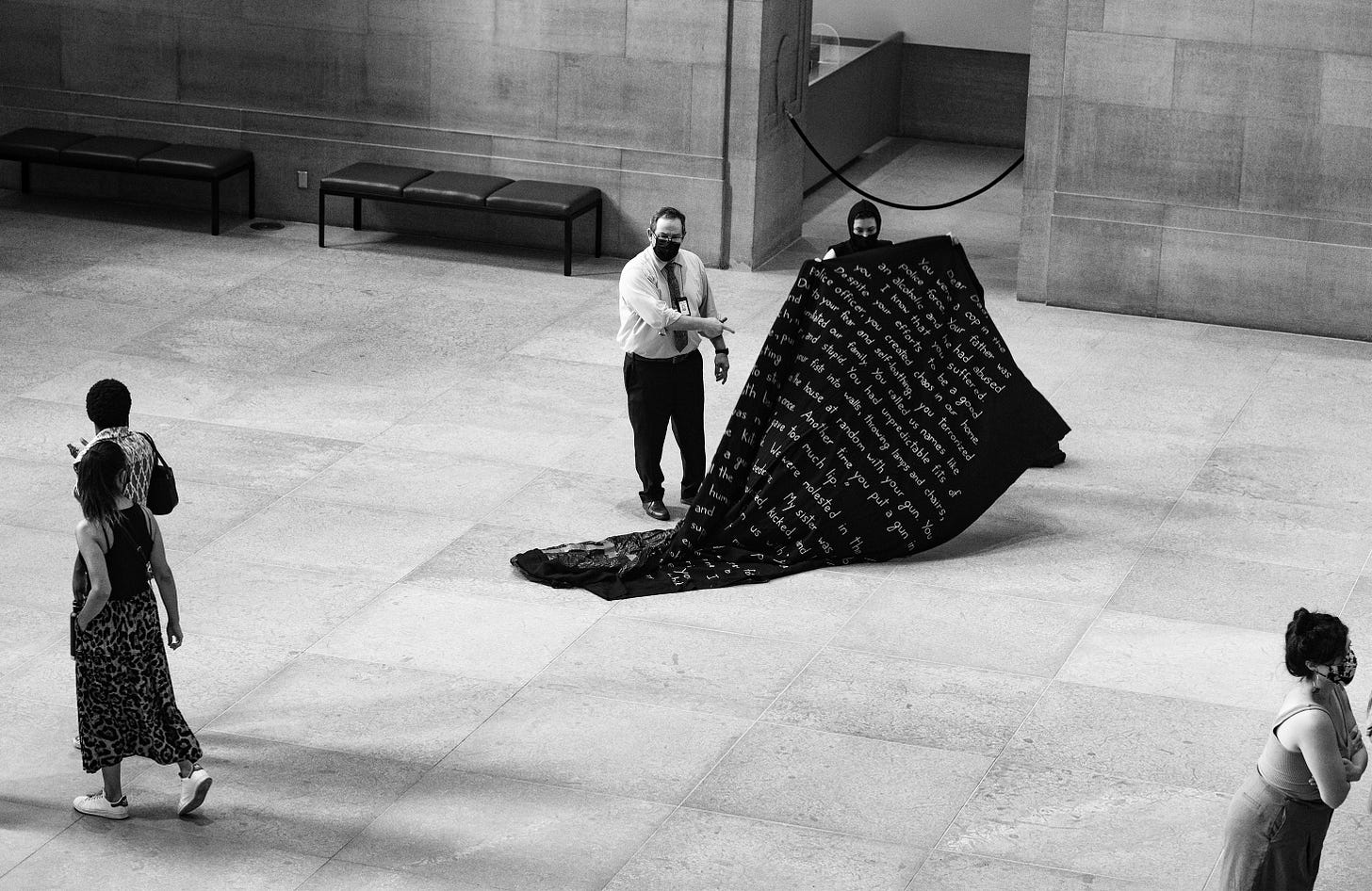

I walked up the steps, went through the entrance doors and laid my cape out on the floor. Immediately, a security guard came over and asked me what on earth I was doing. I told him my usual lines and passed off a curator’s name to delay getting kicked out. Within three minutes, another guard came over, and told me to leave. He was onto my lie, and wasn’t having any of it. That was that. After being there for about six minutes, I packed up and went back outside to the front plaza.

The atmosphere at the top of the museum steps was carnivalesque. The air was thick with a hot mugginess. An older man walked in circles in an urgent state, selling “iccccce coooollld waddder.” He had the coloring of old bark, and he was thin and scraggly. His plea for a sale was like an incantation, and it reminded me of being in India where men on the side of the road sold Chai with a similar sing-song. There were a high number of people milling about too, with, and without selfie sticks taking one pic after the next, running up the steps like “Rocky.” They were posing, strutting, with fists in the air. I went near the center of the stairway, not realizing I had placed myself right next to the plaque of Rocky’s shoes. It was a surprise to me when I discovered this and I didn’t like competing with the plaque of an iconic boxer. Some stood right next to me and jumped up and down conjuring the image of a working class hero. This made me feel very awkward; not seen. I wished I had placed myself on top of the plaque instead.

Sometime in the afternoon, a wedding party showed up, and I could only imagine how aghast they must have been to see me there. I thought this was a pretty damn-dark-funny-ironic situation. When I was a teenager, I had rather cliché concoctions in my mind of what a future family life would be like even though I grew up under my parent’s violent relationship. You know….. a big house, dog in the yard, garden and five children. Five. Children. My family being Catholic, some of my aunts had as many as eight to nine children.

In the 60’s, my parents had been married at a City Hall ceremony, in a small town in France, by “some guy” as my mom described it. The whole ritual lasted about ten minutes, and it was a shoved-through-kind-of thing because my mother was already four months pregnant with a second child. In those days, women were not supposed to have sex until they were married. When my mother was twenty years old, a co-worker accused her of not being a virgin, and having had abandoned a child at a nearby orphanage. Immediately, my mother went to a gynecologist in order to produce a “certificate of virginity.” One can imagine the exam. With paper in hand, she brought it with her to work to correct the false accusations. Catholicism’s heavy, guilty air made sex and shame go together. This isn’t new news to anyone, but obtaining a certificate of chastity truly represents a kind of straight-jacket oppression that I can’t really imagine. “Fucking up” by fucking had overbearing dire consequences for girls and women.

During their wedding ceremony, superstitious tales were being whispered between my relatives too. One misconception was how the weather on one’s wedding day might affect the entirety of your matrimonial life. According to my grandmother, however much rain falls on the day of conjugation will equal the number of tears to fall during your lifetime. When my parents married, it rained cats and dogs, and my grandmother reminded them of what was to come. Recently, I asked my mother if she had any photos. She replied, “No one took pictures.” Such was the gaiety around my mother’s betrothal.

Being in the restaurant and catering world for over 25 years, I witnessed countless weddings, and their aftermath. I saw a bride get drunk and do the worm on the ground in her $1,000 gown. I saw a Russian family drink down bottles of vodka (one full fifth at each table) in rounds of toasts that lasted for hours. They were all still standing by the end of the night with extraordinary ease. I heard the Commodores, Brick House, too many times, too loudly, at too many receptions. Of course, the ceremonious father-daughter dance had made the audience swoon with delight, while I’d shoved down sickly sweet cake or a vodka. Sometimes, I found myself pacing in circles in the handicap stall of the bathroom, taking in gulps of air, exhaling sighs like soft, sweaty songs. Weddings can be exceedingly over-rated, over-priced, and yet, they are also highly charged symbols of success, and happiness.

While I was on the steps, I wondered what this wedding party might be thinking about my cape. One man from the group came over and read my letter. He took his time, opened up my cloak, then he stood near me and thanked me for my presence. His face revealed true empathy. Through my two hours of kneeling, a fair number of passersby talked to me about my project. I was grateful for those who were courageous enough to express their care. One woman implied her father was much like mine. Words truly lack the power to convey over and over again a feeling for the larger connection to all kinds of people in the places I have visited thus far. While much of the bridal party may have been shocked and afraid by my presence, I tried to remain open to those who were curious. I realized as I looked around that each one of us is in a particular world of survival, hope, storytelling, and that we project broad and infinitesimal realities, sometimes with great understanding, and also, with painful misconceptions.